Nadine Dana Suesse (/ˈswiːs/; December 3, 1911 – October 16, 1987)

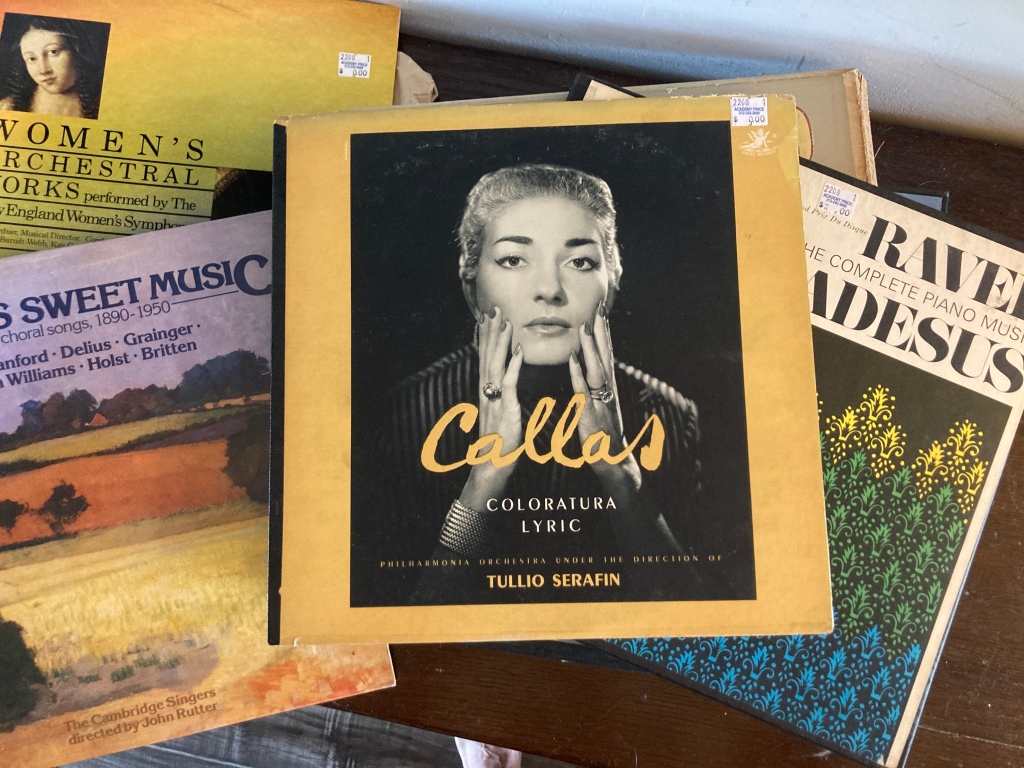

About a week ago, I looked in the local “Little Library” about a block from my house and found a disc called “Jazz Nocturne, The Collected Piano Music of Dana Suesse.” I think a music critic must live nearby, because virtually every time I peer in, someone has left CDs. Those aren’t uncommon finds, of course. What is out of the ordinary, however, is the type of discs my “secret Santa” leaves.

He or she leaves jewel boxes primarily containing classical music. Again, I’m sure that’s not so uncommon. What surprises me, though, is the provenance — a lot of the music are by composers I’ve never heard of. A lot of the discs are by eastern european modern or pre-modern composers. There’s a lot of opera, and while sometimes it’s by composers I know, it might be a piece I’ve never heard of, like Mozart’s “The Dream of Scipione.” There aren’t any present day discs, probably because CD sales have pretty much evaporated with the advent of online streaming services like AppleMusic or Spotify.

When I put on this album, the most extraordinary music popped out. It sounded like a mashup of Ravel, Debussy, Gershwin. These were all the influences of the time, of course, but it sounded so fresh and alive and new. Take the piece below, Scherzette (“whirligig”).

You can read Suesse’s Wikipedia entry and see that she was a child prodigy & a brilliant improviser, she studied with the same teacher as Gershwin, and she had a successful career writing popular songs like “The Cocktail Suite: I: Old-fashioned,” and “You Ought to Be in Pictures.”

I’m happy to find these discs because since there’s only one classical music radio station in my town. That station pretty much cleaves to the standard repertoire of known pieces that they play ad infinitum, which they know aren’t going to upset rush hours drivers on their way to the daily grind (think Vivaldi’s “The Four Seasons,” Beethoven’s “Sixth Symphony,” Rachmaninov’s “Piano Concerto Number 3,” etc.)

If not for the “Little Library” mystery donor, I never would have heard of Dana Suesse. One thing that puzzles, and actually make me kind of angry, is why I had never heard of her before. After I found the disc, I told a friend of mine, and classically trained bass player who’s now also in her 60s like me. She had never hear of Suesse either.

Do any of you know why she never got the kind of recognition after World War II, that people like Gershwin got?